On October 16, the Fed, FDIC, and OCC rescinded interagency principles for climate-related financial risk management for large financial institutions. This is a positive development and a rare occasion when regulators narrow their scope.

There were many problems with the principles, as was pointed out by Vice Chair for Supervision Michelle Bowman. Most importantly, the principles far exceed the narrow mandate of the Fed, which is stable inflation and maximum employment. It is wrong to use financial regulation to fight climate change.

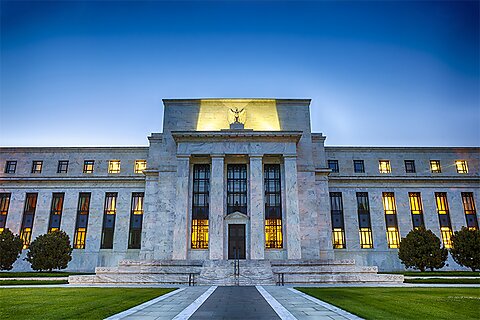

Mission creep into politically charged areas that the Fed cannot directly influence only serves to distract the central bank from its core monetary policy functions. For instance, during the pandemic, the Fed missed its inflation target when it was more focused on distributional labor market outcomes. The Fed was 20 months too late to raise the rate target, which was likely a factor that entrenched and elevated inflation.

Financial institutions already manage risk, and they should focus on those risks that are material to their investors. Diversions into partisan fields such as climate risk are a distraction, and to the extent that climate risk matters, it will already be included by banks in their risk calculations. To the extent that it doesn’t matter for banks’ risk calculations, these requirements lead to distortions in important price signals.

Additionally, unnecessary requirements also lead to unintended consequences such as more expensive or reduced lending due to the added regulatory compliance costs. Not only were firms expected to engage in long-term scenario analysis that stretched far past typical scenario time horizons, but there is also no clarity for the future path of climate-related policy. Vague statements in the principles meant that financial institutions faced unclear expectations and the risk of ever-tightening regulation.

The principles would also focus on “transition risk,” which refers to the risk faced by a firm from a shift to a low-carbon economy. Banks were expected to consider carbon-intensive firms as risky, thus increasing lending costs for those companies. This is problematic because the focus on this risk tries to arbitrarily constrain carbon-intensive firms through financial regulation.

The rescission acknowledges these problems and is a great step in the right direction. Now, the Fed can continue to reduce its regulatory scope and focus entirely on its dual mandate. It should then implement rules-based monetary policy to constrain discretion and create a more stable and predictable monetary regime.